Environmental consultant Sally Linton takes a deeper look at the issue of nitrogen run-off and seepage into our waterways, and what horse owners need to know about it -

“But I don’t have any waterways on my property…” That’s a comment I get frequently when talking to owners of horse properties about reducing environmental impacts that affect water quality. It’s a common misconception that to have a negative effect on water quality you need to be close to a body of water.

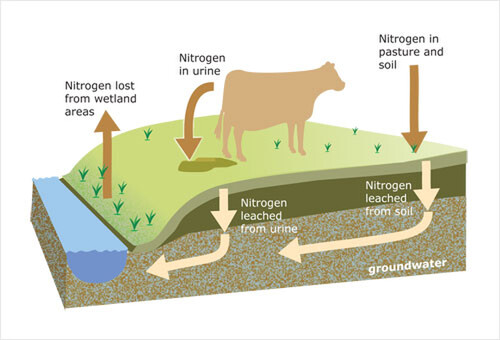

There are two pathways for nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), and contaminants (such as sediment and microbes from faecal matter) to reach the waterways. The first is overland flow to a water body (streams, creeks, lakes, rivers and ponds); the further you are from a water body the less likely run-off from your property will reach it. However, keep in mind that if you have drains they will network and reach rivers and streams eventually.

The other pathway, particularly for nitrogen, is down through the soil itself to the ground water; this will eventually re-enter a waterway. Nitrogen in water, when combined with phosphorus, contributes to growth of water weed and algae. This can make water unsuitable for drinking, and eventually leads to polluted lakes and rivers.

“But I don’t use nitrogen fertilisers on my paddocks…”. It’s true that the majority of horse property owners don’t use nitrogen in the form of fertilisers on their land. As we all know, lush dairy-type pastures and horses are not a great mix, and particularly with ponies and other good doers, fertilised paddocks can lead to behavioural problems as well as physiological issues.

However, even if you don’t apply nitrogen fertilisers, the element nitrogen is present on your farm. Nitrogen is essential for growth in both plants and animals. It will enter a farming system by clover root nodules taking nitrogen from the air and fixing in a form the clover can use. It also enters the farm system in any supplementary feed you give to your horses. Plants take up the nitrogen returned to the soil in the form of urine, dung and leaf litter.

Meanwhile, nitrogen loss through the soil profile to water occurs as horses - like all animals - take in more nitrogen than they can use and it is excreted to the soil, mainly as urine. There will be more nitrogen in the urine patch than the surrounding plants can use, and the excess leaches (seeps) through the soil over time to find ground water.

So, even if you don’t have waterways on or near your property and you don’t apply nitrogen fertiliser, your property will still inevitably be draining excess nitrogen into waterways via ground water.

One of these things is not like the others

Horses are grazing stock, but they are not like cows, sheep or deer. The most significant difference is that cows, sheep and deer are ruminant animals, whereas the horse is a hindgut fermenter. In regard to environmental impact, this means horses utilise nutrients differently. To date, the research on farming systems and environmental impact has focussed on the productive farming sector and its ruminant animals. There has been little research in New Zealand, or internationally, on the nutrient cycling in horses and the resultant nutrient losses from horses or equine farming systems.

The fact that little is known for horses should be of concern for every horse owner in the country. This is because a major current focus of government and regional councils is developing policy and regulations to improve water quality. These policies and regulations will impact all land uses, but have been developed with only ruminant animals in mind.

As a result, it is likely that the rules – particularly in relation to nutrient losses (nitrogen and phosphorus) – will not be appropriate for equine properties, and at worst could severely constrain your equine operation.

What is happening?

While it is completely reasonable to expect that equine properties should manage and minimise nutrient losses, regulation should also be appropriate to the sector. With this in mind, a research project is being developed to better understand nutrient cycling in horses and equine farming systems. The project will be led by Associate Professor Chris Rogers from the Massey University Veterinary School. New Zealand Thoroughbred Breeders along with the New Zealand Trainers Association are strongly supporting this initiative, along with support from Waikato Regional Council. It is hoped that other equine groups such as Equestrian Sports New Zealand and New Zealand Pony Clubs Association will also be involved.

What will we find out?

One of the interesting things that has been found in initial research is that the nitrogen in horse urine is less than it is for cows. This could mean that the impact of horses in relation to nutrient losses is less than cows. However, it is also known that horses graze and utilise pasture differently to cows. Cows generally graze the whole pasture, and will urinate over the whole area that they graze. Horses, in contrast, are selective grazers and tend to urinate and defecate in certain areas where they do not graze, creating the characteristic ‘lawns’ and ‘roughs’. Because they tend to urinate in one area, the concentration of nitrogen will likely to be higher and the nitrogen losses greater, and perhaps cancel out the benefit of lower nitrogen in the urine. The research will get a better understanding with the aim of being able to quantify losses on equine properties.

The aim is to produce a suite of equine-sector specific Good Management Practices, similar to those that have been produced for the dairy, drystock and deer sectors. These will focus on the pasture-based management of horses, which is a unique aspect, and one of the strengths, of the New Zealand equine industry.

What can we do in the meantime?

While research is aimed to provide greater clarity and precision in regard to nutrient losses from horse properties, there are some actions you can undertake now that are known to reduce nutrient losses:

Maintain a good pasture cover and avoid creating bare soil areas. A good pasture cover will utilise more of the nitrogen made available.

Avoid the creation of rough areas by removing dung, harrowing and topping. Alternatively, cross graze with another class of stock such as cattle or sheep.

Get a soil test and only apply fertiliser as required.

Nitrogen will be leached at a greater rate when the soil is water-logged, so if possible keep your horses off pasture during wet periods.

Your dung heap should be sealed (or at least have a lime base) and have storm water diversions to prevent run-off.

If spreading dung back to pasture, do so when pasture is actively growing in spring or autumn to maximise nutrient uptake

Fence off waterways and wetlands

The nitrogen conundrum

What is nitrogen?

Nitrogen, a colourless, odourless element, is vital to the life cycle of all living things. It’s the most abundant element in the air we breathe, (78%) and is also in the soil under our feet and in the water we drink.

Nitrogen is vital for our food supply, but excess nitrogen can harm the environment.

When plants lack nitrogen, they become yellowed, with stunted growth, and produce smaller fruits and flowers. Farmers often add fertilizers containing nitrogen to their crops, to increase growth; however, with too much nitrogen, plants produce excess biomass, or organic matter, such as stalks and leaves, but not enough root structure.

Excess nitrogen can also leach from the soil into underground water sources, or it can enter aquatic systems as run-off. This excess nitrogen can build up, leading to a process called eutrophication, which is the cause of excess growth of marine plants and algae, and can even cause a lake to turn bright green, with a “bloom” of smelly algae, called phytoplankton.

This can lead to a ‘dead zone’ in the water, with insufficient oxygen to support life.

Can eutrophication be prevented or reversed?

Water resources can be managed using different strategies to reduce the harmful effects of algal blooms. Excess nutrients van be re-routed from lakes and vulnerable costal zones, herbicides and algaecides can stop the algal blooms, and there are campaigns to reduce the quantities or combinations of nutrients used in agricultural fertilisers.

Certain plants can uptake more nitrogen, and can even be used as a “buffer,” or filter, to prevent excessive fertiliser from entering waterways. For example, one study has shown that poplar trees (Populus italica), used as a buffer, held on to 99% of the nitrate entering the underground water flow during winter, while a riverbank zone covered with a specific grass (Lolium perenne L.) held up to 84% of the nitrate, preventing it from entering the river.

However, once a lake or river has undergone eutrophication, it is harder to do damage control. Algaecides do not correct the source of the problem: the excess nitrogen or other nutrients that caused the algae bloom in the first place!

In summary

Pollution of our water sources by surplus nitrogen and other nutrients is a huge problem, as marine life is being suffocated from decomposition of dead algae blooms. Farmers and rural communities need to work to improve the uptake of added nutrients by crops and treat animal manure waste properly. We also need to protect the natural plant buffer zones that can take up nitrogen run-off before it reaches water bodies.